O. Winston Link

O. Winston Link | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ogle Winston Link December 16, 1914 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 30, 2001 (aged 86) Katonah, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Years active | 1937–1983 |

| Spouses | Vanda Link

(m. 1942; div. 1950)Conchita Link

(m. 1983; div. 1996) |

| Children | Winston Conway Link |

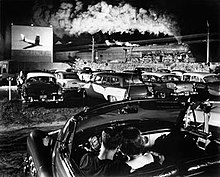

Ogle Winston Link[1] (December 16, 1914 – January 30, 2001), known commonly as O. Winston Link, was an American photographer, best known for his black-and-white photography and sound recordings of the last days of steam locomotive railroading on the Norfolk and Western in the United States in the late 1950s. A commercial photographer, Link helped establish rail photography as a hobby. He also pioneered night photography, producing several well known examples including Hotshot Eastbound, a photograph of a steam train passing a drive-in movie theater,[2] and Hawksbill Creek Swimming Hole showing a train crossing a bridge above children bathing.[3]

Early life

[edit]Link and his siblings, Eleanor and Albert Jr., spent their childhood in the borough of Brooklyn, New York City, where they lived with their parents, Albert Link Sr. and Anne Winston Jones Link. Link's given names honor ancestors Alexander Ogle and John Winston Jones, who had served in the U.S. House of Representatives in the 19th century.[4] Al Link, who taught woodworking in the New York City Public School system, encouraged his children's interest in arts and crafts and introduced Winston to photography.[citation needed]

Link's early photography was created with a borrowed medium format Autographic Kodak camera. By the time, he was in high school he had built his own photographic enlarger.[5] After completing high school, Link attended the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, receiving a degree in civil engineering. Before his graduation in 1937, he spoke at a banquet for the institute's newspaper, where he served as photo editor. An executive from Carl Byoir's public relations firm was present and was impressed by Link's speaking ability. He offered Link a job as a photographer.[6]

Career

[edit]

Link worked for Carl Byoir and Associates for five years, learning his trade on the job. He adapted to the technique of making posed photographs looking candid, as well as creatively emphasizing a point. On his first major assignment, to photograph part of the state of Louisiana in the summer of 1937, he found himself in New Iberia, the location where Cecil B. DeMille's 1938 movie The Buccaneer, about Jean LaFitte was being filmed. Here he met his future first wife, a former Miss Ark-La-Tex, now actress/model/body double, Vanda Marteal Oglesby, who stood-in for lead actress Franciska Gaal. They "took a shine" to one another, and later that year she posed for some of his photographs in the French Quarter of New Orleans.[7] They eventually married in 1942, but later divorced. Some of Link's photographs from this time included an image of a man aiming a gun at a pig wearing a bulletproof vest, and one eventually known as "What Is This Girl Selling?" or "Girl on Ice," which was widely published in the United States and later featured in Life as a "classic publicity picture." According to Thomas Garver, a later assistant to Link, during his employment at Byoir's firm, Link "clearly defined a point of view and developed working methods that were to shape his entire career."[8]

When World War II reached the United States, Link found himself unable to join the military due to mumps-induced hearing loss. He left Byoir's employ in 1942 to work for the Airborne Instruments Laboratory, part of Columbia University. Drawing on his university degree and professional photographic experience, Link worked at the laboratory as both project engineer and photographer. The laboratory was then researching a device to enable aircraft to detect submerged submarines. Link's main responsibility was photographing the project for the United States government.[9]

In 1945, with the end of the war, Link's employment at the Airborne Instruments Laboratory ended. Byoir invited Link back, but Link instead opened his own studio in New York City in 1946. His clients included Goodrich, Alcoa, Texaco, and Ethyl.[10]

Rail photography: Norfolk and Western project

[edit]While in Staunton, Virginia, for an industrial photography job in 1955, Link's longstanding love of railroads became focused on the nearby Norfolk and Western Railway line. N&W was the last major (Class I) railroad to make the transition from steam to diesel motive power and had refined its use of steam locomotives, earning a reputation for "precision transportation." Link took his first night photograph of the road on January 21, 1955, in Waynesboro, Virginia. On May 29, 1955, the N&W announced its first conversion to diesel and Link's work became a documentation of the end of the steam era. He returned to Virginia for approximately 20 visits to continue photographing the N&W. His last night shot was taken in 1959 and the last of all in 1960. That year, the road completed the transition to diesel, by which time he had accumulated 2,400 negatives on the project.[11]

Although it was entirely self-financed, Link's work was encouraged and facilitated by N&W officials, from president Robert H. Smith downwards. Besides the locomotives, he captured the people of the N&W performing their jobs on the railroad and in the trackside communities. Some of his images were of the massive Roanoke Shops, where the company had built and maintained its locomotives.[11]

Link's images were meticulously set up and posed, and he chose to take most of his railroad photographs at night. He said "I can't move the sun — and it's always in the wrong place — and I can't even move the tracks, so I had to create my own environment through lighting."[12] Although others, including Philip R. Hastings and Jim Shaughnessy, had photographed locomotives at night before, Link's vision required him to develop new techniques for flash photography of such large subjects. For instance, the drive-in image Hotshot Eastbound (Iaeger, West Virginia), photographed on August 2, 1956 [negative NW1103], used 42 #2 flashbulbs and one #0 fired simultaneously.[13] Link, with an assistant such as George Thom, had to lug all his equipment into position and wire it up: this was done in series so any failure would prevent a picture being taken. Taking night shots of moving trains the right position for the subject could only be guessed at. Link used a 4 x 5 Graphic View view camera with black and white film, from which he produced silver gelatin prints.[citation needed]

Hawksbill Creek Swimming Hole (Luray, Virginia) was photographed on August 9, 1956 [NW1126]. Other widely known images include Swimming Pool (Welch, West Virginia) (1958 [NW1963]), Ghost Town (Stanley, Virginia) [NW1345], Main Line on Main Street (Northfork, West Virginia) (1958 [NW1966]) and Mr and Mrs Ben Pope watch the last steam powered passenger train (Max Meadows, Virginia) (1957 [NW1648]).[14][15]

In addition to his black and white night shots, Link also recorded the single daytime train on the Norfolk & Western's hilly Abingdon Branch, serving the rural communities from Abingdon, Virginia, 55 miles (88 km) south to West Jefferson, North Carolina. It was also on this line that most of his railroad color photography was done; a selection is included in The Last Steam Railroad in America. His familiar 1956 view of a horse and steam locomotive Maud bows to the Virginia Creeper (Green Cove, Virginia)[16] exists in black and white and color versions.

In addition to photographing them, Link was also making sound recordings of the trains, which he issued on a set of six gramophone records between 1957 and 1977 under the overall title Sounds of Steam Railroading. In the railfan world he was probably best known by these, and by photographs published in Trains magazine and elsewhere in the 1950s, which inspired others to follow his example.[17] The recordings he made from 1957 to 1977 were inducted into the National Recording Registry in 2003.[18]

A traveling exhibition in 1983 brought his work to a wider public[15] as did Paul Yule's award-winning documentary Trains That Passed In The Night (1990), in which Link re-visited the scenes of his classic photographs of the Norfolk and Western.

Later life

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

From 1960 until he retired in 1983, Link devoted himself to advertising. Among notable pictures taken during this period are those recording construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and other views of New York Harbor including the great ocean liners. In retirement, Link moved to South Salem, Westchester County, New York.[citation needed][19]

In 1996, Link's second wife, Conchita, was arrested for (and later convicted of) stealing a collection of Link's photographs and attempting to sell them, claiming that Link had Alzheimer's disease and that she had power of attorney. After being released in 2003, she again attempted to sell some of Link's works that she had stolen, this time using the Internet auction site eBay. She received a three-year sentence.[20] Conchita was also accused of imprisoning her husband.[21] However, this allegation is disputed by some, and it never led to any criminal charges against Conchita.[citation needed] The story of Winston and Conchita became the subject of the documentary The Photographer, His Wife, Her Lover (2005) made by Paul Yule. Conchita died on October 1, 2016.[22]

In popular culture

[edit]Link made a cameo appearance as a steam locomotive engineer in the 1999 film October Sky, operating Southern Railway 4501 (decorated to look like an N&W steam locomotive). He was actively involved with the planning of a museum of his work when he suffered a heart attack near his home in South Salem. He was transported to Northern Westchester Hospital in Mt. Kisco, New York, where he died on January 30, 2001. Mr. Link was interred adjacent to his parents in Elmwood Cemetery, Shepherdstown, Jefferson County, West Virginia.[23]

Museum

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The rail photography of Winston Link is featured at the O. Winston Link Museum in Roanoke, Virginia, which opened in January 2004. The museum is housed in the former passenger station of the Norfolk and Western Railway. Link's N&W caboose forms part of the display.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Link was named after two of his maternal ancestors: the twentieth Speaker of the United States House of Representatives John Winston Jones and Pennsylvanian Representative Alexander Ogle. Last Steam Railroad p. 132.

- ^ This was duplicated in "Dumbbell Indemnity", an episode of The Simpsons (Visual comparison between "Hotshot Eastbound" and The Simpsons scene Archived June 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ O. Winston Link Museum website biography Archived October 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, 1955-8 Archived November 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine . Accessed Oct 20, 2012

- ^ Garver, Thomas H. "A Tribute to O. Winston Link". NRHS Bulletin, National Railway Historical Society. Vol. 73, no. Summer 2008. pp. 3–43.

- ^ Last Steam Railroad pp. 132–3; Museum p. 3.

- ^ Last Steam Railroad p. 136.

- ^ O Winston Link biography at louisianalink.net

- ^ Last Steam Railroad pp. 136-9; Museum p. 4.

- ^ Museum p. 5; Last Steam Railroad p. 140.

- ^ Last Steam Railroad p. 142.

- ^ a b Link, O. Winston (1987). Steam, Steel & Stars. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1645-2.

- ^ Last Steam Railroad p. 20.

- ^ Ghost Trains. It was taken at 1/200 sec. at f11-16.

- ^ "O. Winston Link Museum - 1955". Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Ghost Trains.

- ^ "O. Winston Link Museum - 1955". Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ Brouws, Jeff; Delvers, Ed (2000). Starlight on the Rails. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-8230-7.

- ^ "Steam Locomotive Recordings--O. Winston Link (1957-1977) on loc.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Sholis, Brian (April 1, 2011). "O. Winston Link". Artforum. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ "Ex-Wife's 2nd Trial". May 6, 2004. The Hook. Accessed June 19, 2006.

- ^ "Hell mates: Sad tale of Winston and Conchita"

- ^ "Conchita Hayes - The Putnam County News & Recorder". The Putnam County News & Recorder. November 16, 2016. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ Obituary, The Journal News, February 2, 2001

References

[edit]- Dulaney, Ben (1956). "Flash bulb artist photographs the Norfolk and Western". Norfolk and Western Magazine: 580–3.

- Garver, Tom (2004). O. Winston Link: the Man and the Museum. O. Winston Link Museum. ISBN 0-9710531-4-6

- Garver, Thomas H. (2000). "Railroad photographs of O. Winston Link". American Art Review. 12 (5): 202–7.

- Jones, Malcolm (1999). "The most beautiful trains in the world". Preservation. 51 (6): 30–8.

- Korner, Anthony (1989). "The Night Owl". Artforum International. 27: 141–6.

- Link, O. Winston (1957). Night Trick on the Norfolk and Western Railway. Norfolk and Western RY.

- Link, O. Winston (1983). Ghost Trains. Chrysler Museum. ISBN 0-940744-43-0. ISBN 0-940744-43-0

- Link, O. Winston (1987). Steam, Steel & Stars. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-8185-8. ISBN 0-8109-1645-2

- Link, O. Winston (1995). The Last Steam Railroad in America. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-2587-7. ISBN 0-8109-3575-9

- Morgan, David (July 1957). "The mixed train: photography by O. Winston Link". Trains: 31–43.

- Morgan, David (November 1957). "Steam after dark". Trains: 30–43.

- Oughterbridge, David E. (1989). "Chugging to Extinction". Connoisseur. 219 (935): 122–7.

- O. Winston Link Museum official website

- The works of O. Winston Link

- The photographs of O. Winston Link